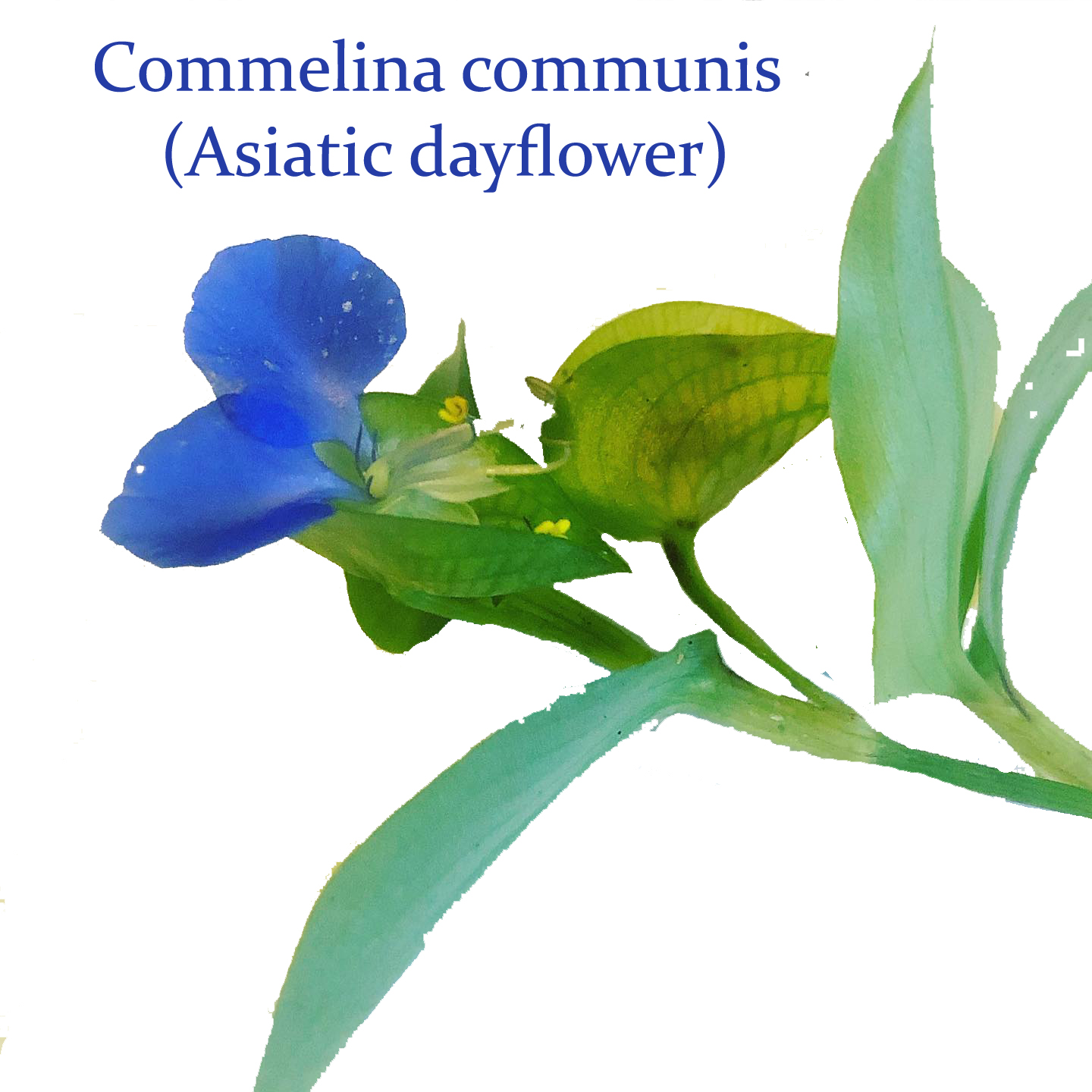

One day I smashed a flower petal from the Asiatic dayflower between my thumb and forefinger. It’s a small plant that grows sparsely in the shady, moist areas along the driveway. While it’s not native to the Ozarks, it is naturalized and I won’t mind using it to make a paint and calling it an Ozark pigment if it passes all the trials. It’s just not a *native* Ozark pigment, that’s all. It was once widely used in Japanese culture for art, and known as つき草 : Tsuki kusa.

Preliminaries

The very blue stain it made on my skin got me curious. And the more I looked into it, the curiouser I got. I smeared that messy finger on a sheet of watercolor paper, and tried to restrain the excited flutters of my heart as I saw the bright blue streak it made. So then I cut the paper down through the streaks and taped part of it on the window outside to get some UV and air exposure. Three weeks later, and the blue is still just as blue as the day it was put there. So this inclines me to believe that it is at the least, a long-lasting pigment. As long as it isn’t made into paint, or exposed to water. In those situations, it’s very fugitive.

That preliminary test gives me hope that this plant might offer me a way to create a locally sourced blue watercolor paint. If nothing else I should be able to make a blue ink from it. And if I have to, I’ll soak the dye in an absorbent paper to hold it in the tradition of the Japanese way (aobanagami).

However, according to my research, the dayflower blue may not be as long-lasting as Maya blue made with indigo. And so that means I will also attempt to grow indigo so I can transition over to that blue pigment later.

What’s the drawback? There’s always something, some price to pay for a precious commodity. With this blue, the price is the time it will take to collect enough of the tender petals to make any significant amount of paint or dye. I need more of the flowers to grow here, and I havent’ found a source for seeds anywhere online. Across the US, this invasive plant grows in copious amounts in some areas. But not right here at Wild Ozark. It took me a week to gather enough petals to make this small amount of extract:

Blue Stability

Apparently there is Magnesium (Mg) bonded to the molecules that make this blue pigment (which is called commelinin, which I believe is a protocyanin type of pigment). I may have misunderstood some of it, but from all I’ve read, it appears that the dayflower blue pigment is stable.

Making the Dayflower Blue

I’ll update this post as I begin making the paint. Right now I’m still trying to gather enough Asiatic dayflower petals to give it a fair trial. It may be the end of next flowering season before I manage to find enough of them. I’m trying to not gather petals every day so that some of the existing flowers can be pollinated and seeds can be produced. The dayflower is an annual, and the flowers only last a short time from morning until around noon, and only one flower per plant each day during blooming season.

A Test Run

090620 Once I gathered enough flowers to make a small amount of paint, I decided to go on and do it rather than wait until next season. Here’s a pan with 2 dried layers of a thin paint made by simply mixing my binder with the extracted blue juice. I did add an equal portion of water to dilute the ethanol, which also diluted the blue. So until I get a lot of flowers, a thin blue may be all I can get. But it’s a beautiful shade of blue, regardless, and the juice from the petals is very rich in pigment. I’ve dried each layer in the dehydrator before adding more. It is drying without tack.

When the next layer is dry, I’ll make a test swatch to see what I can expect in the way of color performance on paper. One thing I already know I don’t really like is the jell-like consistency of the paint due to the alcohol in the initial extract reacting with the gum Arabic in the binder. The next time I do this experiment, I’m only going to smash the petals and maybe use a little bit of water to rinse them, and then go with the blue juice directly.

It may be that this pigment can’t be turned into a solid paint of any sort, and I may have to do it the Japanese way. In that case, I would just soak the petal juice into an absorbent paper. As I’m not sure how the papers are used after that, my plan is to use it directly from the paper by wetting my brush and then using it to wet a small portion of the paper.

But for now, I’m happy with a thin jell to give a little blue to the skies or feathers of my birds!

090920 Update

Well, it didn’t take long to decide to try using the aobanagamione method. I didn’t think I could gather enough dayflower petals to saturate any paper, so tried the binder method first. But then I realized that perhaps I don’t have to soak the paper all at once. Perhaps this is something that can be built upon day by day. And so that’s what I’m trying now. The preliminary results from this experiment are much more promising.

A Test Painting with Dayflower Blue

On Oct. 18, 2020, I cut a tiny little snip of the corner of that small blue square pictured above. I put it in a tray and wet it with a mop brush to see if the dayflower blue would come out of the paper. It did! This is the very first painting, done in my little journal, to see how the blue worked as part of a sky. It’s not a ‘paint’ so it doesn’t perform like paint. It’s more like a dye, and soaks into the paper. I haven’t done anything other than this test painting, though, but I think it’ll work for a lot of my blue needs, but I have to remember it stains the paper wherever I put it. I won’t be able to manipulate it as I can the paints. I’m quite excited to have this new color in my palette.

What is the Significance?

My goal as an artist is to only use the pigments I’ve foraged myself, and to not buy or import any materials. At the moment, I do still buy the binder gum (Gum Arabic) and my paper and brushes. But all of the pigments I use are sourced from what I’ve found locally. The stones, clay and bone are all strictly Ozark native colors. The dayflower is not native, but do grow here naturally now that they’ve become established in our region. Until now I’ve simply done without blue in my palette.

The indigo will be a departure in that it’s a plant I’ll have to actually grow in my garden and not one that I’ve wildcrafted. But it will be ‘Ozark’ in the sense that the leaves will be gathered right outside the door. And so I will accept that departure in order to have semi-permanent blue in my repertoire. However, while lapis lazuli isn’t an Ozark pigment, it is an earth pigment and permanent. So, as of 2024, I’ve begun using that for my source of blue in my oil paintings.

See More of My Art

Click here to go to my portfolio of work. I don’t use the blue often because it’s so time intensive to produce, and I can’t use them to make oil paints. You’ll find it in some of the work before 2023.

References

- https://ukiyoereproduction.com/post/624867656174043136/%E3%83%BCabout-making-method-of-aobanagamione-of-the

- Takeda K. Blue metal complex pigments involved in blue flower color. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2006;82(4):142-154. doi:10.2183/pjab.82.142

- Shiono M, Matsugaki N, Takeda K. Structure of commelinin, a blue complex pigment from the blue flowers of Commelina communis. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2008;84(10):452-456. doi:10.2183/pjab.84.452